What is your relationship with anger? Is it a familiar companion that shows up to defend you at the slightest trigger? Or is it more like an estranged family member that appears only when absolutely necessary? Are you aware when it shows up, or does it take over in the blink of an eye, transforming you before you even realize it? Do you wish it would show up more often? Do you wish it gave you a warning so you could tame it before it runs wild? Is it like a natural disaster, wreaking havoc and leaving nothing but destruction? Have you been hurt by your own anger? Have others been burned by its wildfire, intentionally or unintentionally?

I’ll be honest. I used to feel uncomfortable with anger—that hasn’t completely gone away, but I’m working on having a healthier relationship with it. I used to think it was good that I didn’t let myself get angry, but I learned over time that anger is an important emotion. By denying myself access to anger, I was also denying myself important information that could be invaluable to my growth and transformation. I know I’m not alone in this. Many women have been socialized to be “good” and “nice” to put others at ease, even if we feel like a volcano ready to erupt. We have been taught to contain our anger regardless of how justified we are in expressing it. We learn to be considerate of others even if it’s an inconvenience or harmful to ourselves. When others tell us we are agreeable, we are supposed to take it as a compliment, even though it feels like we are constantly last on our list of priorities.

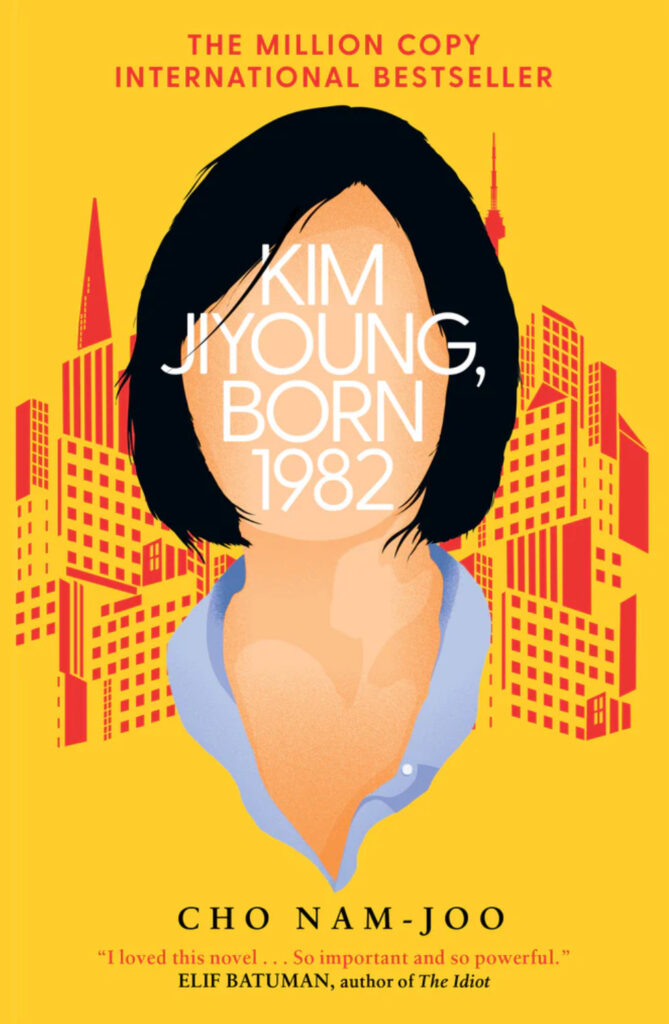

I recently read the novel “Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982” by Cho Nam-Joo. It inspired me to write about anger and reflect on my relationship with it. For most of her life, Kim Jiyoung learned how to behave and uphold the values of a patriarchal society. When a boy bullied her in elementary school, she was told it was because he liked her, a very dangerous lesson to teach young girls. Even as a child, Kim Jiyoung found this illogical and wrong. When she was harassed by a male from her academy at night, her father blamed her, teaching her another dangerous lesson: it is your responsibility to anticipate and avoid dangerous situations. If you don’t, then it’s your fault, not the perpetrator’s. You should have known better. You brought it upon yourself. You earned this punishment. So Kim Jiyoung quit the after-school academy and learned to be scared of men. While still in university, looking to secure employment before graduation, Kim Jiyoung was asked by a male interviewer how she would handle being harassed by a client. She responded that she would find a natural way to leave the room. To get the job, given the obvious power imbalance, she felt pressured to provide an appropriate answer—thinking about how to make it less awkward for the client rather than asserting her own boundaries. In the end, she didn’t get the job and deeply regretted not answering truthfully—the answer that probably would have come from anger. Like most of us, Kim Jiyoung was not taught how to use her anger to speak up for what she believed. Eventually, when Kim Jiyoung got married and became pregnant, she had to quit the job she enjoyed and found meaningful to stay home and take care of her baby girl. While everything pretty much stayed the same for her husband, Kim Jiyoung’s life had to be completely altered because that’s what women are “supposed” to do. We accommodate, sacrifice, and put everyone else’s happiness above our own as if it is the natural way to do things. And we’re supposed to do it all with a smile. After 34 years, Kim Jiyoung stopped smiling and saying yes, and for that, she was diagnosed with a psychological disorder.

After reading this powerful story, I wondered what would have happened if Kim Jiyoung had been allowed to feel her anger. Anger is a misunderstood emotion. It’s a hard emotion. If you’re like me, Kim Jiyoung, and many other women, you have probably set limits and barriers around it. It may take longer to reconnect with your anger. According to Clarissa Pinkola Estés, inviting anger back into our lives will take patience. Are we ready to hear what it has to tell us? Are we ready for the change it will ignite inside of us? Are we ready to act on the information it gives us? This is why patience is necessary. We can imagine our anger as a bear coming out of hibernation. Initially, it might be groggy and lethargic—it needs to regain its strength and energy. It is also very hungry—imagine not being fed for years. How do we nourish the anger that’s been starved for so long? I think we begin by listening patiently and compassionately. We need to call upon our compassionate self to sit with anger. It might not want to speak to us at first. It might act out like a rebellious teenager. This is why patience is important—it’s about building trust with this part of ourselves again. With time, the hard shell of the anger may slowly start to soften, and underneath, we may find hurt, pain, and sadness. The compassionate self can finally validate the anger and bring it out of its hibernation. After listening patiently and validating, we may ask anger what it needs from us.

I believe that one of the needs that may arise after we repair our rupture with anger is respect. Anger deserves our respect. It is not dramatic. It is not overreacting. It is not too sensitive. These are messages we may have internalized as women. Anger has an important message—it is here for a reason. I think one of the reasons we may keep anger in hibernation is because we were never taught a healthy expression of it. Maybe all we’ve seen is people hurting others when they are angry—lashing out, yelling, shouting, insulting, degrading. This may create a fear in us that if we let our anger out, it will become a loose cannon, harming whatever gets caught in its crossfire. Fortunately, that does not have to be the case. Anger, like every other emotion, has important information to share. It may be telling us that our boundary has been crossed, that we’ve been hurt in some way, that our rights have been violated, that our wants and needs have not been met, or that we have been derailed from our goal and need to return to our course. If Kim Jiyoung could feel her anger, I think it would tell her: “Stop! You’re giving up too much!” “Enough! You don’t have to take this crap anymore!” “No, you are not crazy!” “You have finally come out of hibernation.” “It’s time to start living your life!”

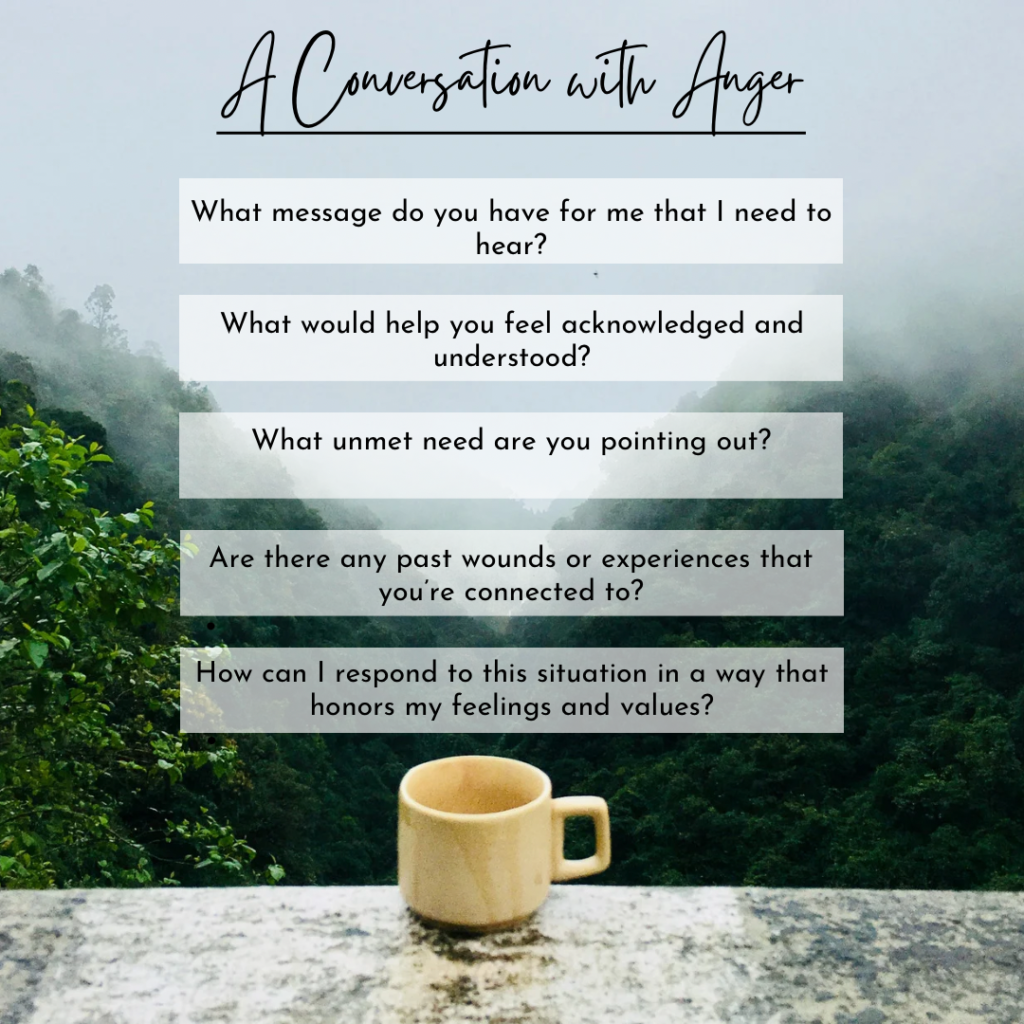

Are you curious about what information your anger has to share with you? I hope you follow this curiosity and ask questions with an open heart and compassion, and hear, maybe for the first time, what anger has to tell you. I know it can be scary, and you don’t have to do it alone. It’s okay to seek help and work with a professional. Be patient and be kind to yourself. If you’re ready, you can start here: